Representing the Self, Improperly

Milica Trakilović

Introduction

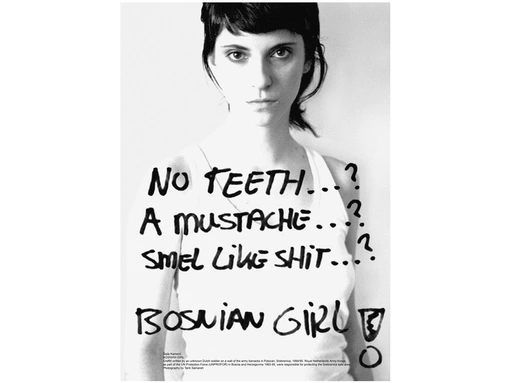

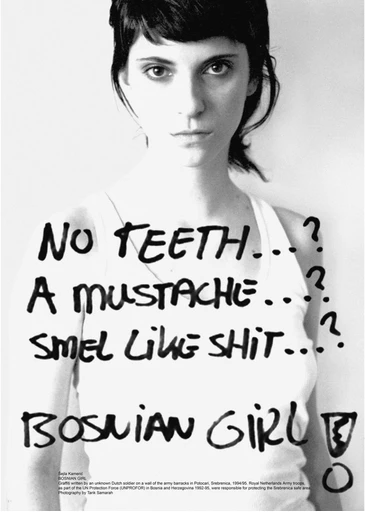

I can no longer recall the first moment when I saw the black-and-white photograph that you are looking at. In some ways, it feels as though I have always been acquainted with it, but this is not actually the case. Over the years, the artwork Bosnian Girl has become a red thread of sorts that weaves my personal trajectory and academic repertoire together, and thinking and speaking about this work has become, in a sense, effortless, organic. However, I do remember that there was a time when the work had a profound, piercing effect on me, but when I could not grasp how or why that was; I could not articulate what it did (to me), nor why that was important.This is no longer the case. Throughout my feminist academic trajectory, I have assembled a theoretical and analytical toolkit which has given me two important things. Firstly, a critical lens through which to understand and assess the workings of power and social inequalities. Secondly, a vernacular and poetics—ways in which to communicate the meaning and significance of these understandings.

In this text, I want to illustrate how this process of sense-making and articulation has developed for me, in the hopes of encouraging you to look for your own analytical toolkits. I will be doing that by drawing on feminist and post-colonial approaches to representation,

Constructionist theories of meaning say that the production of meaning is never a static enterprise. According to these theories, meaning is not just ‘out there’ in the world for us to be found and interpreted. Rather, meaning is something that is constantly being made; it comes into being. Stuart Hall, a founding figure of the field of cultural studies, has argued that meaning is negotiated in and through a complex network of exchange and interpretation, a process which is never finished.

Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, 2nd edition (New York: Sage Publications, 2013 [1997]).

Coined by postcolonial scholar Edward Said, Orientalism speaks of an ideological construct which has its origin in European colonial history and still has wide-spread effect in the present.

Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

Other existing ideologies interact with the Orientalist meaning and deepen it further, such as the discourse of Balkanism. Theorised by Bulgarian feminist scholar Maria Todorova in 1997,

Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009 [1997]).

Keywords:

representation, mimesis, feminist art, Orientalism, Balkanism, cultural studies

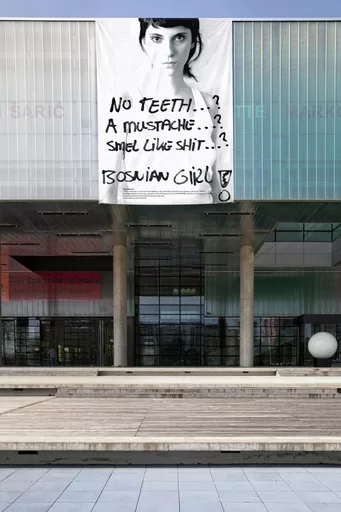

Contextualising Bosnian Girl

Bosnian Girl is a work by the Bosnian artist Šejla Kamerić from 2003. It is a black-and-white photograph of the artist herself looking directly into the camera with a serious, piercing expression. Over her image, a large portion of graffiti text is positioned that reads ‘No teeth…? A mustache…? Smel like shit…? Bosnian girl!’ The text is harsh, arresting, and seems to stand in stark contrast to the stylised image of the young woman we are looking at. At the bottom of the photograph, there is a portion of text in small print that gives further information about the graffiti text: it was made by an unidentified Dutch soldier in the period of 1994-1995 on the army barracks in the town Potočari.This location is very close to the town of the Srebrenica, where more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were murdered by Serb army forces in July, 1995. The Dutch troops had been stationed in the area at the time to protect the Muslim population. Yet, this promised protection had failed and resulted in the first case of genocide in Europe since World War II.

There is an ongoing effort by activists, artists and scholars to create more awareness about Srebrenica and to make it part of the Dutch cultural canon. See the website srebrenicaisdutchhistory.com/ for further information and context.

In August 1995, I was eight years old when I fled the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina with my family and sought asylum in the Netherlands. What followed for me was a period of disorientation and adaptation to a new language and culture, as well as alienation due to never properly fitting in. I think the word ‘proper’ is significant here and may be part of the reason why Bosnian Girl gripped me years later and has not let me go since. During my childhood in the Netherlands, I never felt myself to be ‘properly’ Dutch in how I spoke the language, performed the cultural customs and participated in the social context I had come to inhabit.

The word ‘proper’ carries a lot of meaning. In Bosnian Girl, the graffitisuggests that being unclean, uncultured, unappealing (in a word: improper) are faculties that make a girl Bosnian. This, I believe, explains why the image has resonated with me so. I recognised some of my own experience in it, and felt some vindication in being seen, even if it was unpleasant or uncomfortable. To be clear, the vindication does not lie in recognising myself in the demeaning image of the ‘Bosnian girl’ in the graffiti. Rather, it’s the artist’s grappling with that image that struck a chord of familiarity. The recognition has to do with someone else experiencing and addressing the prejudice you are familiar with.

However, Bosnian Girl has never merely represented visibility for me, but, more importantly, an overcoming, a refusal of the very stereotype that is printed in big letters over the image of the artist. Although the picture is arresting, this is not a static image; it moves. In order to understand how this works, I consider in what follows how a stereotype can be taken up and turned around on itself.

When two opposites are placed next to each other to highlight their inherent difference, they cancel each other out in a sense. In this way, opposition implies rejection. Looking at Bosnian Girl through this lens, we can certainly argue that the artist employs the strategy of opposition/rejection—she opposes the image in the graffiti (dirty, debased, masculine, uncivilised, barbaric, anonymous, etc.) with the stylised image of herself (clean, polished, feminine, stylised, particular), thereby rejecting the original meaning.

This intervention is relatively straightforward to grasp. However, there is a deeper layer of meaning that can be teased out that places the artwork’s significance not in the rejection but rather in the inclusion of the intended meaning, thereby diluting or even nullifying its message. In order to understand how this works, we need to draw on theories that will help articulate the critique that is inherent to the work.

Meaning and Ideology

Constructionist theories of meaning say that the production of meaning is never a static enterprise. According to these theories, meaning is not just ‘out there’ in the world for us to be found and interpreted. Rather, meaning is something that is constantly being made; it comes into being. Stuart Hall, a founding figure of the field of cultural studies, has argued that meaning is negotiated in and through a complex network of exchange and interpretation, a process which is never finished.Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, 2nd edition (New York: Sage Publications, 2013 [1997]).

Coined by postcolonial scholar Edward Said, Orientalism speaks of an ideological construct which has its origin in European colonial history and still has wide-spread effect in the present.

Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

Other existing ideologies interact with the Orientalist meaning and deepen it further, such as the discourse of Balkanism. Theorised by Bulgarian feminist scholar Maria Todorova in 1997,

Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009 [1997]).

Creating Alternative Meanings; Trans-Coding and Mimesis

One of the ways in which Bosnian Girl disrupts the original meaning of the graffiti is by employing the strategy of trans-coding. Stuart Hall has described trans-coding as the process of ‘taking an existing meaning and re-appropriating it for new meanings.’Hall 2013, p. 259.

Hall 2013, p. 263.

Hall 2013, p. 264.

Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’ (New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 37.

In Bosnian Girl, the artist mimetically occupies the stereotyped image that is outlined in the graffiti. This disturbs the original meaning, since the Bosnian girl in the photograph (clean, stylised) does not correspond to the image in the graffiti (unclean, improper), and because the artist gives the Bosnian girl a face, instead of anonymity. Moreover, she is not supposed to be the speaking subject and certainly not the one to (re)produce this image. In a patriarchal society, ‘men act and women appear,’ as visual scholar John Berger so aptly put it.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: BBC/Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), p. 47. www.ways-of-seeing.com/

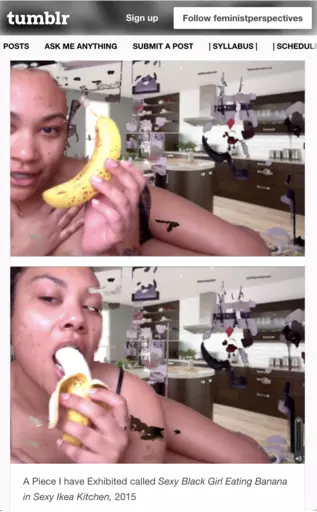

The Body as Critical Instrument; Situating the Subject and Viewer

Kamerić joins a long tradition within feminist art where the artist’s body is used as a tool for critique. The significance of such strategies lies in the fact that the critique is rooted in materiality and experience; the critique has a location and a position of enunciation. It does not pretend to be universal; the particularity of the critique is what makes it transgressive. Feminist scholarship has produced substantial critique of notions such as neutrality, objectivity and universality. Such notions can be dangerous because, in a traditional sense, they presuppose that objectivity, neutrality and universality exist and/or can be attained.However, as noted feminist scholar Donna Haraway has pointed out, all knowledge is partial and biased, and therefore incomplete. To claim that universality exists, or that one can attain complete, objective knowledge, is to perform what Haraway calls the ‘God Trick.’

Donna Haraway, ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,’ Feminist Studies vol. 14, no. 3 (1988): pp. 575-599.

Consider how this works in the case of Bosnian Girl; here, the graffiti expresses a condemnation of, supposedly, all Bosnian women/girls. The message in the graffiti is presented as a fact (emphasised by the exclamation point in the end). The fact that the author is unknown reinforces the ‘truth value’ of this exclamation and enforces its unquestioned, undisputable character. The God Trick is employed to produce a ‘view from nowhere,’ which gives a seemingly definitive statement about the appearance and status of all Bosnian women and girls.

Kamerić interrupts this logic by stepping into this image, not from a position of transcendence or anonymity, which has traditionally been associated with masculinity, but from an embodied position which produces a situated, accountable vision. Her intervention is both particular (representing herself) and carries a community aspect with it (she is one among many Bosnian women). This intervention is an example of the famous feminist credo that says ‘the personal is the political.’ Yes, this is a particular image of the artist herself, but it also makes a political statement that seeks to challenge the sexist and cultural stereotyping that was left in the graffiti. This makes it possible to recognise her image in its specificity (this is the artist herself) and to simultaneously feel invited to participate in the refusal of the original message by considering how it relates to the particularity of your own experience, as was the case with me, as I recognised myself in the rejection of the ‘improper’ discourse.

Amelia Jones, ‘The “Eternal Return”: Self Portrait Photography as Technology of Embodiment,’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 27, no. 4 (2002): pp. 947-978.

This opens up the production of meaning to a never-ending circulation as well, urging us to conclude that there is no final definition of who the Bosnian Girl is, and neither can the soldier be simplistically categorised as the ‘villain’ of this story. As such, the element of pure opposition becomes muddled, as it becomes clear that this is not actually, or not only, a standoff between Kamerić and the unknown soldier. Rather, Bosnian Girl is an involvement of the unspecified collective, which includes you as well, in the never-ending process of interpretation—a humbling and life-affirming enterprise.

Conclusion

In this text, I have unpacked the multi-faceted meanings of Bosnian Girl by asking how a stereotype can be taken up and turned on itself. I have first explained how existing discourses, such as Orientalism and Balkanism, are part of the original graffiti message and how this makes it ideological rather than incidental. From there, I have explained how Bosnian Girl performs an intervention into these dominant meanings. I have shown how the work makes use of trans-coding, mimesis, embodiment and employs the strategy of ‘the eternal return’ to displace the harmful meaning in the original message.Ultimately, I believe the work’s significance lies in this: it opens up the circulation of meaning where previously it had been foreclosed (the message in the graffiti appears finite, undisputable). In so doing, Bosnian Girl not only produces critique, but also hope—that change is possible. And indeed, it is, as I have shown through the conceptual tools that I have drawn on, which all, in one way or another, have demonstrated how meaning-making is a contested phenomenon (since meaning is never fixed) and a power-laden enterprise (since meaning is informed by social norms and power).

Representations in particular can enforce ideologies, but can also contest existing norms, sometimes in unexpected ways. This article has explored those strategies of resistance that engage with harmful stereotypes, not through rejection but close association with that very stereotype. I have assembled a specific analytical toolkit to articulate the extent of the critique that Bosnian Girl performs. This interpretation is not definitive, but it is substantial because it is grounded in both a critical feminist framework and personal experience, which makes for a multi-faceted analysis and an open-ended (rather than closed) reading. I hope this interpretation can be grounds to inspire you to assemble your own critical toolkits. What will they consist of?

Online Course

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of anWant to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

The entire

Want to delve further into the topic of this essay? Then take a look at the corresponding lesson that is part of an online course that consists of 10 lessons based on the 10 essays in this publication. These lessons focus on the central concepts that are treated in the essays and are followed by various questions, assignments and/or work formats.

The entire online course, including an extensive introduction, can be found via the button below. If you want to go directly to the assignments for this essay, click here.

I can no longer recall the first moment when I saw the black-and-white photograph that you are looking at. In some ways, it feels as though I have always been acquainted with it, but this is not actually the case. Over the years, the artwork Bosnian Girl has become a red thread of sorts that weaves my personal trajectory and academic repertoire together, and thinking and speaking about this work has become, in a sense, effortless, organic. However, I do remember that there was a time when the work had a profound, piercing effect on me, but when I could not grasp how or why that was; I could not articulate what it did (to me), nor why that was important.

This is no longer the case. Throughout my feminist academic trajectory, I have assembled a theoretical and analytical toolkit which has given me two important things. Firstly, a critical lens through which to understand and assess the workings of power and social inequalities. Secondly, a vernacular and poetics—ways in which to communicate the meaning and significance of these understandings.

In this text, I want to illustrate how this process of sense-making and articulation has developed for me, in the hopes of encouraging you to look for your own analytical toolkits. I will be doing that by drawing on feminist and post-colonial approaches to representation,

Constructionist theories of meaning say that the production of meaning is never a static enterprise. According to these theories, meaning is not just ‘out there’ in the world for us to be found and interpreted. Rather, meaning is something that is constantly being made; it comes into being. Stuart Hall, a founding figure of the field of cultural studies, has argued that meaning is negotiated in and through a complex network of exchange and interpretation, a process which is never finished.

Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, 2nd edition (New York: Sage Publications, 2013 [1997]).

Coined by postcolonial scholar Edward Said, Orientalism speaks of an ideological construct which has its origin in European colonial history and still has wide-spread effect in the present.

Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978).

Other existing ideologies interact with the Orientalist meaning and deepen it further, such as the discourse of Balkanism. Theorised by Bulgarian feminist scholar Maria Todorova in 1997,

Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009 [1997]).